Recently I began work on a project to manage the deployment of a product built using a microservices architecture. As a result of our chosen architecture we have a large number of services which will communicate to each other over HTTP/S. Instead of using fixed IPs we decided to used DNS SRV records to indicate where services could contact their dependencies. Today’s post goes into using SRV records in a little more detail and the problem they solve.

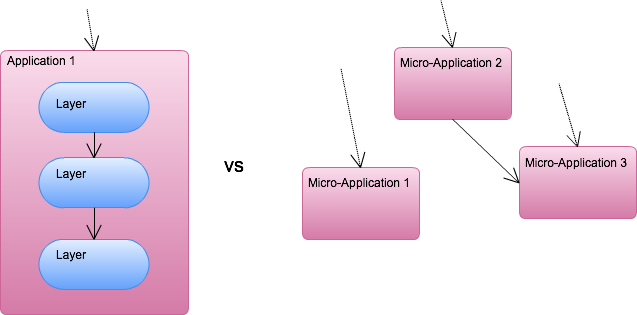

I have not commonly seen true dynamically deployed microservices architectures. To be specific, true, is in the sense that the applications within the systems could be deployed, updated, or migrated without human intervention or disruption. I suspect that this is because end to end build, test, and deploy automation is hard. We’re trying to do the hard thing (automated build, test, and deploy), and do it with a microservices architectures which means that we must deal with a large number of components that must be built, tested, and deployed.

Build and, in particular, test in this type of distributed environment can become difficult, but for now, let’s focus on deployment. Naming and name resolution are important considerations for the microservices environment; this boils does to how does service A know how to make calls to service B?

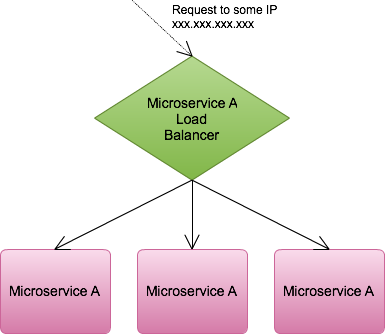

A naïve solution may be to run each service on a fixed host and port (and fixed IP address). The IP and port combination for each service would then be given to dependent services as a piece of configuration. A slightly better approach would be to use a load balancer with different configurations for each microservice. The load balancer is a better approach since then at least we can start thinking about zero or minimal downtime deployments.

Unfortunately, with the load balancing approach any environment of significant size will still yield a number of essentially magic addresses and port numbers which correspond to applications.

In a managed on premises data center it might be okay to have IP addresses in configuration. In an infrastructure as a service environment, however, particular IP addresses may come and go over time breaking applications. In addition, it just seems like a good idea to give well known names to applications instead of just referring to them by IP address and port number.

DNS records as a solution

Introducing a DNS server and assigning names to hosts is a good start to resolving the above problems. DNS provides us with human friendly names for hosts (appserv01.hosts.dc1 instead of 192.168.1.254 for example.) Additionally, BIND, among other DNS servers, has supported dynamic updates to records for some time now. Dynamic DNS updates gives us the ability to maintain a name over time while the underlying hosts change address. ‘A’ records are intended to only solve the problem of mapping host names to IP addresses though and don’t handle port number allocation.

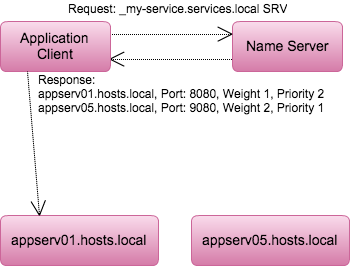

In the last 15 years another record type was added to the DNS standards, SRV. SRV records were intended from the outset as service locators and combine some useful properties into a single record. SRV records associate a name, _myserver.services.dc1 for example, with both an A (or AAAA) record and a port number. A DNS server may also have multiple records for a particular service name with different priorities, allowing for seamless fail-over strategies.

This type of DNS record is already widely used for chat clients; Microsoft Lync, Jabber, and others use SRV records to locate endpoints. The strength of the SRV records derives from its ability to identify the complete location of a service (IP and port) and be updated dynamically. In the above diagram another record for another instance of the service could be added or one of the existing records could be removed without making it unavailable to dependent applications.

Returning to microservices, DNS SRV records are an appealing solution to one of the architecture’s problems. SRV records give us a way to put dynamic names on large interconnected service inventories. Unfortunately, some (many?) applications will need custom code to intelligently handle SRV responses. This means that using SRV records with existing or legacy applications might be difficult, even in scenarios that might otherwise make sense. For new, heavily interconnected systems though, SRV records do make sense even when some custom handling code has to be written.

Wrap up

Some times and places to use SRV records:

- microservices architectures that communicate in some fashion on top of TCP

- When you have control of the nameservers for the environment and what human readable names for both hosts and services

- When your applications have large number of external dependencies named using IP addresses or similar

Some times and places to not use SRV records:

- When there isn’t an easily way to control the records returned by your name servers

- In environments with a small number of larger applications (costs of setup in this scenario likely outweighs the benefits)

Hope this article helps bring some ideas to the table for how to have microservices name and communicate with each other. A future article will look at one particular way of setting up DNS in an environment for use with SRV records.