Have you ever considered a service or suite of services and thought, “that looks like a ball of yarn.”

There is a tendency amongst those of us who write software for a living to consider systems that are not understood as garbage. Often, this suspicion of poorly understood systems turns out to be unwarranted. What look like obtuse decisions made for no apparent reason turn out to have solid foundation in rationality. Software that looks strange with weird functionality sometimes is that way because strange and weird things were asked of it.

This post is not about rational decision making. It is about the figurative balls of yarn. The systems that really do need help.

When considering a system we talk about quality indicators like the the inner platform effect or design anti-patterns. Poor quality can lead to slow development and other issues, but may not be a problematic enough to warrant planned rework and refactoring. I like to use a couple other indicators:

- Rising extension costs: If the cost to extend the system rises linearly, or worse, exponentially, with respect to the number of features added then the design and implementation of the system may no longer be appropriate for the use cases that it needs to support. This is probably the most important indicator.

- Ornate designs: Another indicator of a failing system is when architectural or design purity insists that long and unnecessarily complicated paths are taken to answers instead of simple straightforward approaches. We’ll come back to this one in more detail because it’s one that I have seen frequently and it often leads to rising extension costs.

Costs

Actual times to completion on new work can be indicative of growing problems in a code base. We can split work costs into two categories, significant one time investments and work that increases the cost of future work. The innocuous kind involves trying to satisfy new unexpected use cases with existing tools. For example, if a system has RESTful style APIs but exposes XML documents then a one time investment would be adding support for JSON to existing APIs.

On the other hand, if the construction of the system is such that adding new features costs more for every (possible unrelated) feature then it may be time to re-approach how the system is structured. A couple examples,

- A micro-services architecture where multiple services are tightly interconnected such that individual services are not independent. This system becomes more expensive to maintain overtime due to the need for changes across multiple services in order to implement every new feature. Improving this design can mean moving functionality between services in order collocate future changes.

- At the other end of the spectrum are large single service solutions that have been extended to support multiple customer use cases. Generally, adding new features becomes more expensive over time due to the cumulative complexity of changes to the service. There are ways to refactor and avoid this, ironically, one option is split the functionality across multiple microservices.

It’s worth noting that the reasons for cost increase are myriad. For example, fixes for the above scenarios are not just different but opposite, one is to combine elements of the system and the other is to break apart elements of the system. While there are many causes for high feature cost, the one I have personally seen the most is unnecessarily complex service design.

‘Ornateness’

Ornateness is a broader problem than implementation costs. When present in sufficient quantity it can lead to high development costs, but time can be saved if it is detected beforehand and rectified. The definition of dangerously ornate is also harder to precisely define than high development costs. With this in mind let’s consider a couple examples.

HATAOS and HAL in extreme

HATAOS combined with HAL is a design approach for enabling self-discovery in HTTP web API clients. An API enables clients by returning responses that contain links to other related data and services in the system. The approach can make writing interactive clients, such as browser applications, significantly easier than APIs design that return isolated sets of data.

A problematic application of the pattern though involves a service making multiple HTTP calls to itself in order to retrieve data that it (the service) managed. This makes performance of the design somewhat unpredictable since a single HTTP call may result in tens or possibly hundreds of self referencing HTTP calls. This is HAL and HATAOS taken to a logical extreme; if a response can include discovery information, why not make the service that returns the response fully dynamic and use the response it sends to discover more information from itself.

The result is a service that can handle only one class of business use cases and no other (without significant work).

Incorrectly applied language and framework idioms

Another example of ornateness is a service that took a non-idiomatic usage of a language and framework too far. JavaScript can be used as a object oriented (OO) language, in the past I’ve written some tips on the best approach to this.

With things like JavaScript and OO patterns it is vital that the design paradigm be used in the context of the language and not the other way around. For example, design decisions that make sense in the context of a sprawling application written using a class based language like Java may not make sense in the context of Node.JS microservice. In fact, it may be damaging to maintainability to use approaches such as creating DI containers (not the same as inversion of control which is generally good to follow), extensive abstract base ‘class’ prototypes, and (pseudo) interfaces. The added layers of abstraction which help simplify a class based application tend to be less helpful in highly dynamic tools like JavaScript. Additionally, patterns like creating large base prototypes and DI containers can make applications written using dynamic languages hard to maintain because they obfuscate (by abstraction) the location of logic within the application.

The two examples show different sides of the same problem, introduced complexity that did not add any new functionality. On one hand a service was made more complex by not knowing where to stop when applying a design pattern and on the other a service was made significantly harder to work with due to non-idiomatic patterns and practices.

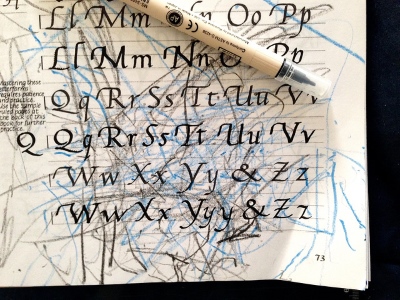

In the end some systems just look like this,

A system can be difficult to work with due to failures in understanding when and when not to apply design patterns or due to accumulated features. It could also be that things needed by the latest and greatest customer are hard to implement in the existing system because of old design constraints or assumptions. In any case, these may be signs that the system needs significant planned maintenance. To stop from going on too long we’ll leave for another day ideas for how to approach planned maintenance of a software system.

I hope these couple items, cost and design complexity, stand out as things to watch for on current and future projects.