In this post I give a short explainer on how federal income taxes function for individuals along with examples of why they are complicated. In a follow on post to this I will cover some thoughts about how we, collectively, can help make it simpler.

Some changes in my life recently caused me to review which federal and state tax deductions and credits are available to me. My search turned up a few that are applicable. This post isn’t about my personal tax situation though; it is the beginning of a rant about why I had to perform a search for deductions and credits at all.

In the beginning there were progressive taxes.

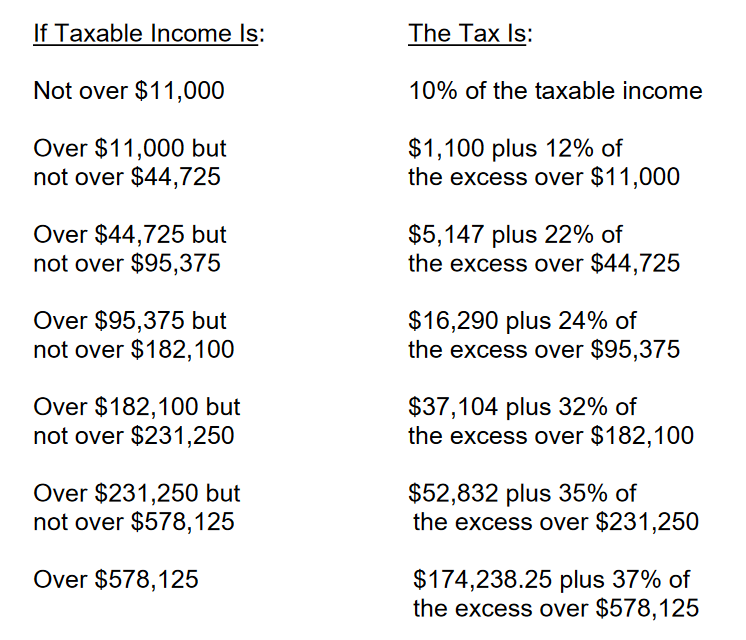

This is not progressive in the political sense. The federal tax system uses progressively increasing tax rates based on annual income. My impression is that how progressive tax rates work is frequently misunderstood. Fortunately, the IRS has documents showing how this works for individual income taxes.

This 1040 Tax Table PDF provided directly by the IRS provides precalculated amounts of tax owed for some of the most common incomes. Additionally, every year a rates publication is released with all of the updates to rates and amounts used for taxation in that year. For 2023 it is a PDF found here.. A screenshot of the rate tables is below.

To make it concrete, a single individual, John Doe who makes $35000/year would owe $3980 in federal income tax annually (specifically, $1100 + (35000 - 11000) * .12). This makes for an effective tax rate of 3980/35000 or ~11.4% and a marginal rate of 12%. Note the difference well, often in layman’s discourse over income taxes the difference is lost. The marginal tax rate is much easier to define and argue about on the likes of Twitter, but is also almost always not what individuals actually pay. This is relatively simple so far.

But the table header says ‘Taxable Income’…

Deductions and credit take this simple table and make it significantly more complicated. The income tax we pay at the federal and state level is based not on the amount of money we ‘make’ in a year, but a much more nebulous calculated number based on deductions and other factors. The most common of these is known as the ‘Standard Deduction’. Deductions work by reducing the amount of money that counts towards taxable income. In the above example, John is instead taxed on $21150/year of income instead of $35000/year because the single filer standard deduction is $13850. John’s taxes owed become $2318 (1100 + (35000 - 13850 - 11000) * .12) for an effective rate of ~6.6%. Note that John’s effective rate is now almost half of his marginal rate.

The standard deduction is one example, there are many, many, many deductions which apply to different situations in a person’s life.

That last link mentioned something about credits…

It gets more complicated. Independently of deductions, the federal tax code also offers credits. A tax credit functions by reducing the amount of tax owed. Let’s suppose John is also a single father with one child and meets the rules for the ‘Earned Income Tax Credit’ (EITC). John could then get a credit up to $3995. John’s owed federal taxes would now be $0 since the credit value of $3995 exceeds $2318 and his effective tax rate would be 0%. There’s more to this since the EITC is refundable and John could receive money back resulting in a negative effective rate, but we won’t address that here.

Like deductions there are many, many, many credits which apply to different situations.

Why the credits & deductions

The US tax code has quirks that seem present to help incentivize certain behavior,

- We like to support families having children so we have things like the ‘Child Tax Credit’ and the EITC.

- We prize property ownership so we include deductions for interest paid on mortgages.

- We strongly encourage entrepreneurship so we allow deductions of business income from businesses owned by individuals from personal taxes.

- We want to encourage electric car ownership so we provided a (very large) tax credit for purchasing a new electric vehicle.

The downside to this approach is complexity. The downside is compounded by the requirement that individuals compute their own taxes from scratch. I can’t speculate why we do this in the US compared to other western democracies, where tax authorities pre-compute common tax situations. The result though, is a filer in the US must be aware that credits, such as the EITC, exist in the first place and correctly file (digital or physical) paperwork to claim them. The situation has gotten marginally better recently with IRS’ Free File which is available to many, many filers based on income. However, I wonder if we can do better.